Senufo - Blog

The Kodal mask

The Kodal is a Senufo mask often wrongly describted in literature. You can read that the Kpelié is a sub-group of the Kodal masks or that the Kodal is a topic of certain Senufo masks. Burkhard Gottschalk explains the term Kodal on page 127 of his book "Senufo - unbekannte Schätze aus privaten Sammlungen" that the Senufo call all masks Kodal, when they have no ritual meaning and are danced in public, or masks from other tribes used in own ceremonies. Many information got mixed up to create a synonym or a basic term for countless types of undetermined Senufo masks. There is a number of Kpelié masks describted as Kodal in the book "Die Kunst der Senufo, Museum Rietberg" by Till Förster from pages 34 up to 43.

While I was writing my books, I found a lot of confusing information, especially from the named sources. So this blog article does show, for the first time, an explizit example of the Kodal.

The Kodal is a distinct mask on its own and is always in combination with a costume suit. The Kodal mask characterizes the panther. The dance is called "Boloye" ("la danse panthère") and everyone in the village is allowed to see the panther dancing. The dance to traditional Senufo music is for entertainment on ceremonies as for baptism, weddings or a man enters a new initiations phase. It is documentated that also kids dance in panther costumes together with the adult men. Mostly there are five and more dancers in a variation of prints.

This shown mask has two round shaped vents that allow the dancers to see. The eyes are cutted out and the edges show hand stitches to avoid fringing and to give more expression to the eyes. In the corners of the square shaped sack, two ears are seperately placed in the each corner. The mask does have two plastic lenses form sunglasses inserted and fixed in the corners of the cloth by hand stiches in a blue yarn.

The group of the dancing panthers "Boloye de Koko". Koko, a village next to Korhogo, March 2019. Photo by Souleymane Arachi.

The full-body costume, mask and suit is always separate, itself is like a "Onesie", a one piece suit. There are only seams in the side, arm and the inseam of the legs. Some have a long zipper in the back, simpler versions do show a binding in the neckhole. The arm itself is set in Kimono pattern. The cut in general is rectangular like, only the inseam is in a curved line. Tassels made of raffia are at the hem of the feet.

The suit has a baggy cut, with overlengh arms. You never see the hands of the dancer.

The silhouette is, like any other ceremonial costumes of the Senufo, exaggurated and should not be human like. Sometimes the dancer holds dry limbs in his hands to express stalking.

The most characteristic feature of the Kodal is the material: Handprinted cotton fabric. There is a wide range of certain designs. Some should imitate fur or spots, others show strong geometric patterns.

The Kodal covers the complete head and neck. The shown fabric does have printed circles, persumibly made with bottle tops and a geometrical stripe pattern in dark brown and red.

Content and images by Markus Ehrhard, 29.07.2020

How to determine the age of a Kpelié mask?

No matter which tribe, we all confess that some masks that look freshly made turn out to be very old. And, and that is mostly the case, very old looking masks were probably made last year or even last month. It is extremely difficult and nearly impossible to determine an age of an african sculpture (Sure, we all know these online experts, who can tell you right away the date of origin just by an image of an object, without having a mask in their hands and without comparing it with other authentic masks. Honestly, do you really believe that? Or is it just what you want to hear?).

Since I published the three books and went online with this archive, no week without inquieries and questions about the age of masks and statues. In one of a hundred cases, I can determine a carver. But in all the other cases I can and will not say anything just by an image. Many objects look authentic, but to be sure an object has to be compared with other objects of the same genre in real.

Yes, a provenance might be helpful, as long the information about the pre-owners is true and not faked itself. At least a provenance tells you the date, when a piece first entered a collection or got traded, but it still does not give you a hint, when, where and by whom it was actually made. So many times I see "masterpieces" with a list of owners, mostly galerists and mainly that famous old French Collection where the name is a big secret, because of "discrétion" (which stinks), and even the tribe is not known. I never saw any original shipping or custom documents that did proof, at what time a sculpture was imported. Do you?

Rarely an old photograph is the ultimate proof, where a person like Helena Rubinstein or a Man Ray photograph holds a piece or you can spot a sculpture in the back of such an image. But in the era of Fake News we are aware of what Photoshop and Gimp can do with an image. Am I too critical? Yes, I am, because there are too many possibilities to fake an object or the history in this demi monde scene. Again and again people contact me who spent outrageous amounts of money for crap. Like in life, think, before you buy an object, and don't believe. In case you have the slightest doubt, don't buy it. And compare, compare and compare again. And compare not just via an image, compare in real.

I said that many times before, the Kpelie mask of the Senufo tribe is not a rare mask. You still find old authentic masks for reasonable prices (to give you an idea: I do not spent more than € 1.000 for an undamaged mask made before 1945 from a known carver. Sure, there are breathtaking Christie's and Sotheby's prices, but these results do not show reality. If that would be the case, I would certainly life in Fort Knox).

In case of the Kpelié there are certain style elements characteristic for certain periods and regions. Old decoration designs surely got repeated till today. But there are differences. When Bolope was one of the carving centers of the Senufo before 1950, many masks did have a wing as a center piece on top (read my blog article: The Bolope Wing). It can not be clarified, what these dynamic shaped designs stand for, but this style feature is typical for that region and time. Having said that, it is surely possible that recent and faked masks can have this wing element. But during my years of researchings, I never saw a foul mask with this specific decoration. From my point of view as a designer, this wing is simply not interesting for an airport art mask which is made for sale.

A stylistic sign for a recently carved mask are the triangular and semi circle shaped decoration elements on each side of a Kpelié, which show a plain surface and no carved decorations like rills. These masks don't even look pure and modern, these styles are typical for a time period from 1970 till today.

Typical for an old mask from around 1900 to 1940/1950 is, that they often look unfortunate, clumsy and crude. Ok, nothing easier than faking this too, but have a look and see the following examples of old Kpelié masks made by known and unknown Senufo carvers. The dating was possible only by comparing the masks with masks from the same origin (carver) and region (all the shown masks are from the west of Korhogo and south of the Mali border).

Karl-Heinz Krieg collected this mask carved by Melié Coulibaly (died 1952 in Landiougou). The time of creation is around 1920. The face is wedge-shaped with a pointy chin. The Kpelié does show a typical crude style for this time and region and the carvers's abilities.

The carver of this Kpelié is not known or documentated. It was collected by Karl-Heinz Krieg 1980 in Siempurgu. He dated this Kpelié around 1930, after a comparison of the patina, style elements, the wedge-shaped face and proportion, as well as the elaborated carving technique with other masks of that region.

Zanga Konaté died 1940. Karl-Heinz Krieg collected this Kpelié 1990 in Sonovelle. Comparing three other masks from Zanga, a Kpelié with a Tugubele pair on top was very similar in its elobarated style, we were able to date a time around 1920. An earlier carved mask by Zanga was not as fine as this.

This mask was easy to determine, because more than 10 masks in exact the same style are known by Fossoungo Dagnogo. He died 1973 in the age of 79, so it possible to evaluate certain levels of his skills.

Masks he made in his early years are flat, like this shown one from around 1940. The face is more graphically than sculptural.

Karl-Heinz Krieg did collect this Kpelié, made by a Koulé, 1969 in Nafoun. The mask is heavy and chunky, and not carved fine or elegant. The clumsy style, the featured elements and the patina are typical mask for a time before 1950.

This Kpelié mask was carved by Kadohognon Coulibaly, who died 1953 in Bolope. At first view this mask doesn't look antique at all. There is a small damage on one of the decoration elements. Persumibly it is a reserve mask, that was owned and protected by the family over the years. The dating is between 1920/1930.

Songuifolo Silué, died 1986 with 72, is a very famous carver. In more than 50 years of working, he left a huge amount of all kind of sculptures. Karl-Heinz Krieg did a profound documentary about Songuifolo. We were able to date the time of origin from 1935 till 1939. Silué was already precise in his technique, but he hasn’t found his final proportion.

Sidekick information: Masks with damages.

Yes, danced masks can have damages such as broken decoration elements or parts, especially parts around the fixing holes, of the edge on the back of a mask can brake. That surely can be an indicator, that a mask was used in ceremony, but it is not a proof. Karl-Heinz Krieg wrote in his book "Kunst und Religion bei den Gbato-Senufo, Elfenbeinküste" in an own chapter, page 68, about the "ugly mask". After a mask received severe damages, the broken "ugly" mask will dance by the Plakoro, a character who got satirized. A damaged mask is not beautiful anymore and the audience will laugh.

Dear galerists, you and I, we all are interested in good and authentic pieces. Right? Very often you offered me damaged masks with the argument, that this is a sign of an authentic piece, because it shows traces of dancing. That might be the case, but, as said, it is no proof. Vice versa offering you a damaged mask, all of a sudden it has no value to you at all. So let's play fair. No?

Dear collectors, the best advice I can give: Simply avoid to buy a damaged mask or any other damaged object! It has no value at all!!!

Note 1:

After posting this article in Facebook groups dealing African art, I received certain critics, that I, as a collector (who had 8 semesters of art history as subject in my studies of design and did a total of six years of intense researching as author for three publications and a number of articles for a German tribal art magazine) doubt experts opinions. One post even got deleted. That’s right, I criticize certain experts on purpose, because I find the way of judging, evaluating and determine an object very difficult. Sure, there might be lifelong experiences and gained knowledge over a long time. Sure, that some sculptures stand out by craftsmanship, patina and artists expression. Sure, there are many objects, that cry out loud that they are fake. But giving an expertise or to determine an age or date of origin just by a photo or to say „Sorry, fake!“ without giving any proof of evidence why exactly this object should be a fake, or not to give a hint to comparing or documented objects, neither giving a source to a book, catalogue or to a website, is simply unserious. And I find it even more dubios, when these, and I set the quotes on purpose, „experts“ sell sculptures. Bashing down others objects just to sell yours is...how to say that nicely...just not cool!

Note 2:

The ultimate and academycally certified proof is the radiocarbon method.

Copyright content and images by Markus Ehrhard, 12.02.2020

A study of symmetry

Please let me tell you right away, that this is not an article, where I try you tell/sell you, how to apply the Golden Ratio in an African sculpture. The Senufo carvers do not excercize these rules in their objects. In retrospect, depending on the size, the Golden Ratio application surely works on almost everything that we conceive as beautiful. You see what you want to see. The following consideration is different, much simpler...and, trust me, even more impressive.

Certain times I explained the purpose that the Kpelié mask is to entertain the audience. And a beautiful, elegant and perfectly carved Kpelié arouses admiration. Everyone loves symmetry.

Keeping in mind, that the shown masks are hand made with simple tools, it is very impressing, how delicate and filigree these objects are carved by a masters hand. For their size, they are incredibly light in weight. The hollow in the back is very deep and the body of the mask is extremely thin. A closer look reveals a stunning accurate and precise symmetry. Both sides are perfectly mirrored. Every detail is in line and in the exact way on both sides of the mask.

After I received the first mask made by Bakari Coulibaly from Dickodougou, my thought was that he used templates. It is documentated that sculpturers like the Fono, who made Kpelié masks in bronze, made mug-ups of clay or wood on which they formed their wax prototypes. All their masks, like Gobé Koné from Gbon or Tiénlé Gobé from Landiougou, have the same size and proportions. Only the decoration elements differ.

My persumption was, that Bakari worked out a template with the proportions of the face, where eyes, nose and mouth are placed together with the positions of the side elements and repeats these on following masks. Bakari, today is his 50ies and not carving anymore, was strongly influenced by his famous father Drissa Coulibaly, who still lives in Korhogo. But after comparing a second, third and fourth mask made by Bakari, the setup, construction and the body volume of each mask was different and composed in individual proportions. He certainly worked with rulers and a triangle ruler, but his tools like hatchets, knives and blades were traditional.

Most of the Kpelié masks, especially antique ones, are carved by eye. Often the decoration elements are not in angle or the eyes or mouth are slantwise carved. There are also masks where one side of the face is broader than the other side. The technique is up to the carver. Less ambitioned sculpturers of the Senufo were not focused on symmetry, the spiritual power of the final object is more of importance. In many interviews these carvers explain, that the spirits let them do that, which is an easy but also honest answer.

But symmetric masks, like the masks from Bakari Couilbaly, or his father Drissa Coulibaly, or from Songuifolo Silué or Sabariko Koné always stand out. Songuifolo Silué did carve the shown Kpelié (mask on the right) when he was in his early 20ies. Even as a young sculpturer he was driven to create a nearly perfect work. The only element that is not in the center is the mark on the forehead. But the study shows, that all other features are perfectly mirrored and balanced.

It is even more delicate to carve two identical faces, like Bakari Coulibaly did of the doublefaced Kpelié (mask on the left). Meassuring this is mask, every single detail is in line and absolutely symmetric. The precision of a mask can not only be an indicator for an authentic mask reliabel to a carver, it can also be an distinctive attribute to the outstanding character of the carver itself and his artistic sense and awerness. And Senufo carvers can be very ambitioned and driven to create handmade perfection.

Content and images by Markus Ehrhard, 07.04.2019

Yêchikpleyégué, doublefaced Kpelié mask, carved by Bakari Coulybali, *ca. 1965, Dickodougou.

33,5 x 15,0 x 9,5 cm, wood.

Literature:

not published yet

Kpelié mask, carved by Songuifolo Silué, Fono from Sirasso. *1914 +1986.

Time of creation between 1935 - 1939.

40,0 x 16,0 x 10,0 cm, wood. Former Karl-Heinz Krieg collection.

Literature:

- Wenn Brauch Gebrauch beeinflusst, Markus Ehrhard, pages 96 - 101.

- Kunst & Kontext, Ausgabe 07, 2014, page 39.

- Kunst und Religion bei den Gbato-Senufo, Elfenbeinküste, Karl-Heinz Krieg und Wulf Lohse, page 46 - 49.

- Aus Afrika, Ahnen - Geister - Götter, Jürgen Zwernemann und Wulf Lohse, Seite 65 - 66.

- Afrika Begegnung, aus der Sammlung Artur und Heidrun Elmer, page 67.

Distinct formulation

About the collective memory of the Senufo and the individual characteristics of their carvers - summarized and structured by name in the first online archive. Rarely does one learn the name of the carver for an African sculpture. This can have ritual backgrounds that an object may not be created by human hands. However, it is commonly said, that an African sculpture is handled anonymously, that is without a name assignment of the originator. The prices of the tribal-art market are based artificially and are not artisticly based.

Endless are the most emotionally held discussions about authenticity. Endless also the number of supposed experts who give ratings on the basis of a photo views in social media today, without having actually held the sculpture in hand or compared it with other objects of the same genre. There are many faked pieces around, that is beyond question. But it is, in the era of Fake News, very easy to claim that an object is a fake without having to prove it. And once described as a "fake", this rating remains, even if an authenticity to the originator can be detected. Todays artists are economically orientated, organized and optimized brands. Names such as Damien Hirst and Ai Weiwei not only present themselves as visitor magnets in the exhibitions, but are a guarantee of a "secure" inverstment, althought these artists have rarely made their works by their own hands.

Repeatetely I have experienced that the mention of an African carver really does not interest collectors, traders or scientists. Quite often I have heard racist and disrespectful remarks against a carver. However, the information about the originator is the only interesting thing and lets clarify the question of authenticity on its own. My mentor, Karl-Heinz Krieg, who lived for decades with the Senufo, inspired me for the Kpelié mask. Quickly I specialized in this type of mask and directed my collecting on masks with assignment of the carver. Karl-Heinz documentated the individual carver and wrote me once as dedication "The artists should speak directly to us". And that is exactly what I want in my books and with my online archive.

The beauty of mass

I call it "the crust" (abb. 1). The first sight of my wall with Kpelié masks has a disturbing effect, mask beside mask in St. Petersburg hanging form a structure, you hardly see the underground. I am fascinated by the beauty of the mass, the collection by re-ordering order, seeing the whole and then experience the effect of each mask with its specific details. A good Kpelié combines the expression of strength and elegance. Some Kpelié masks are very elaborate which reminds me of my work as a designer for the Haute Couture in Paris. It brings the craft and stylization to the edge of the possible a human hand is able to do.

The Kpelié mask of the Senufo is not a rare mask. Every small Senufo settlement has a repertoire of masks that are danced on occasions such as the birth of twins, funerals, or in the secret society of the Poro, where only men are allowed to see the mask. Also men and male children only are allowed to dance in the Kpelié. Every seven years these masks get exchanged for new masks with the same spiritual effect. The Kpelié represents a spirit and shows different genres, such as the double faced, the comedien or the Kpelié with the large Calao bird. The word Kpelié, asking today's carvers, is "face made of wood". Koulé (other spellings are Koul, Kule, Kulebele or Koulebélé) describes the profession of the carver, a Daleguee is a Koulé, who is allowed to carve the Kpelié mask. It can also to be seen that a Koulé was often productive for up to 60 years, producing more than 1.000 sculptures such as masks, statues, household items like spoons and containers, tools and furniture.

The comparison as a method

An insightful consideration is the comparison. This presupposes is having a certain amount of objects to compare. By specializing in a particular theme or genre, collecting fulfills this requirement, such as the Kpelié masks or the Tugubele statues of the Senufo. By comparison as a method, sculptures from profound works can be determined and attributed to the carver (Koulé) or forgeon (Fono or Loko, who also work in wood). An assignment based on a single object is difficult, unless the carver shows an incomparable handwriting in his work.

Comparing several objects of the same genre or a range of the same carver, the development and the artistic awareness become obvious too. The Kpelié mask has not changed significantly over the last 150 years. Even today this mask is getting produced, with all its characteristic features, danced and sold.

Conservation by repetition

Traditionally, a Koulé learns his craft from his father. At the age of 10 to 12 carvers like Ziehouo Coulibaly (born 1941) from Korhogo or Zié Soro (born about 1945, died in 2020) from Djemtene started as a helper to learn their craft. According to the individual work steps, they were led first by sanding an object, and later in the learning process to complete an entire sculpture. Many Koulé are related, so nephews or cousins were trained within a large family. There are also so-called carving schools in Ouézomon (founded by Sabariko Koné), Kolia or Nafoun. Throught repetiton of the sculpture, the artistic awareness of the carver itself is formed, as well as the collective memory of the Senufo culture. One must also consider the matter of fact, that a certain amount of literature such as books and catalogues are run by carvers to repeat their sculpture.

Nuances in the repetition

In the constant repetiton of the sculpture, the formal language of the individual carver forms and develops. Individual conceptions of shape and proportion formulate the own style and consiseness. Senufo carvers do not sign their work. The carvers are well known in the society and so-called masters can be famous public personalities and their work characterize the appearance of the sculpture in the region. There is a competitive situation within the Koulé group: The one who makes a beautiful mask or an imposing statue can be sure not only of fame,

but also receiving follow-up orders.

Tchètin Bêh Konaté, a Koulé who died in Zanguinasso in 1996 at the age 76, has only Tugubele and smaller Nyingife statues known (Nyinigife are small guardian figures belonging to the group of Tugubele spirits and are prescibed to private persons by a diviner). He first learned to carve from his father Zanga Konaté, who died 1940 in Zanguinasso, so Tchètin Bêh moved to Ouézomon and completed his apprenticeship with a relative, Sabariko Koné.

The 20-year-old carver quickly adapted the form and style of his new master and developed his own design features, such as the spoon-shaped ears or the flattened line along the spine of his Tugubele statues. Throughout his life, Tchètin Bêh remained faithful to his proportions, even with oversized figures (Abb. 2). His work has held at the same level of quality for decades, which in turn makes dating difficult or impossible to draw conclusions about a specific phase of his work.

Traditional attributes as a trademark

The hairstyles are distinctive for a typical Senufo carving. Striking are the beaded braids that sit on the forehead and on the sides (the Senufo name them Su or Sû). Jewelry as well as three- or five-row ornamental scarves arranged in a star shape around the navel or in formations on the face are further distinguishing features of a Senufo sculpture. A hatchet or sword in the hand a male Tugubele, as well as a rice bowl in the hand of a female firgure, are also cultural objects that find symbolic power and recognition in the sculpture. Furthermore, traditional signs may also be the primordial animals of the Senufo, such as the chameleon, the turtle or the python.

A striking feature of the recognition of a carver is, for example, the Tefala-Ndong, a straw-woven hat of a wise farmer. This wide-brimmed headgear not only serves to protect against the sun, but is also a symbol of wise action in the cultuvated field of the Senufo.

In the figurative depiction of the Tefala-Ndong is also a symbolic feature of its symbolism, from which one can draw assignments and conclusions on the carver. The master carver Bakari Coulibaly from Dickdougou is famous for his opulently designed head covers of his equestian figure (Syonfolô). The hats of the little Nyingife statues by Zélé-Zana Coulibaly from Sienré are rather simple in design and are considered his trademark (Abb. 3).

Distinct formulation

Same place, same time and two carvers: Nono Koné (d. 1970) and Wahana Dairassouba both lived as Koulé in Tiogo, southeast of Bolope. Both show the same composition and the same shape in their Kpelié masks (Abb. 4), all in the traditional and established style of the Senufo. Even details such as the decorative triangular embellishments on the sides of the masks, the down-hanging pairs of legs and the rectangular shaped mouth with rectangular hatching are identical in shape and expansion.

Apart from these traditional features of the Tugubele couple and the Calao bird on top of the masks of Nono Koné and the two Kapok fruit features on top of the masks of Wahana Dairassouba, a differencation was made from the artistic awareness of the two carvers. Nono formed his decorative elements circular shaped, Wahana presented his masks with a semicircular and angled shape. A distinguishable form formulation is used this case as a distinctive feature of a carver.

A proportion study

A Koulé or Fono of the Senufo does not go throught the study of human anatomy like artists and designers of our culture. Also the formulas and rules of the Golden Ratio are not known and are not applied in the creation.

Songuifolo Silué (born about 1914, died 1986), a Fono of the Kafibele from Sirasso, developed in addition to the traditional style also statues and masks in its own, so-called pure style. Silué was a well-known carver of the Senufo. He was accompanied by Karl-Heinz Krieg for years, extensively documentated and described as a master. He actively created over 60 years an enormous number of sculptures. It is likely that due to the high demand he developed this pure and simple style in order to efficiently produce sculptures both for traditional use and for commercial use. His three Nyingife statues (Abb. 5) show in a propotion study that they were all well carved in the same proportion at different sizes.

This, in my opinion, testifies a special artistic talent and consciousness, which I compare with the absolute hear of a musician. Due to ist inimitable execution in the proportions to each other, his sculptures can de safely assigned.

Der Sabariko-Koné standard

The carver Sabariko Koné (died 1949), a Koulé of the Gbato Senufo, decisively shaped the collective memory of the Senufo sculpture. His developed archetype determined the shape of other carvers of his and later times. He was the founder of a carving school in Ouézomon and made scuptures for the use in ritus as well as for commercial reasons. Like all the Senufo carvers did and do the so-called Airport-art.

The comparison (Abb. 6 and Abb. 7) shows a Tugubele couple carved by Sabariko Koné after 1930. Beside a work of his diciple Tchètin Bêh Konaté (born about 1920, died 1996), Koulé of the Niene Senufo from Zanguinasso (both authentic couples come from a diviner of the Niene from Nadara, next to Boundiali). Furthermore, in comparison, a representation of Fono Ponzié Coulibaly from Pitangomo and an early work by Yalourga Soro, a Koulé from Ganaoni, region of Nafoun.

In juxtaposition all couples show extremely short legs, which are sometimes more, sometimes less worked out in the form of a logical anatomy. The buttocks show a definition represented by a groove, probably an apron or hip jewelry. In contrast, the overlong torso with outstretched bellies, correspondingly covered long arms with shortened and forward curved forearms the hands are in the same position of the tight in all figures.

The basic silhouette is given by Sabariko Koné. Other Koulé and Fono of neighboring subgroups of the Senufo did not copy but adapted and established this style. Also in this comparison, the individual nuances in the repetition can be seen, which lead by the own interpretation, impelementation possibility and handicraft abilities of the individual carver to its handwriting.

For example, the two Tugubele of Yalourga Soro show different shapes of the two heads. Especially in couples, the carver is very keen to carve identical heads and faces to convey the unity, that these two statues belong together. In contrast to Sabariko or Tchètin Bêh, Yalourga shows a different level of craftmanship in his works.

Masterpiece versus Ordinary

The term „masterpiece“ is now in the scene infaltionary in use. Sometimes it describes a particulary rare piece, sometimes an outstanding carving and sometimes just a justification for a high price. The "masterpiece" has become stylized by its title.

The Kpelié mask by Bakari Coulibaly from Dickodougou is an example of a special artisitc exuberence that can be described precisely and symmetrically as well as harmoniously composed as an outstanding masterpiece within the extensive repertoire of Bakari himself.

In comparison, a work by Melié Coulibaly (died 1952), Koulé from Landiogou: This mask is an example of a simple, almost rudimentary work that is just as authentic and correct as the mask of Bakari. Even a simple object experiences holiness through its form and stands no less in ist spiritual effect in rite Abb 8).

„The spirits let me carve the figure like this"

It turns out to be very difficult to get the right information about an object. I did not personally visit the region west of Korhogo to do my researching locally. I do not need to do that to work out my study of differencation, shapes and proportions. Today I work with Souleymane Arachi from Korhogo. He is charged with visiting living carvers and asking questions translated into the respective Senari languages. It has been found that questions from our art historical point of view, as in words as well as in context, can not be translated.

Questions about wether as a carver distinguisehd between an young and older women in sculpture are answered in most cases as follows: "The spirits make me carve the figure like this."

In many conversations with Karl-Heinz Krieg, he explaines his problems in his interviews, which he conducted during his travels directly on site. He, as a white man, often received only the information he wanted to hear abount an object, so to speak. Or also that some carvers showed up in his presence even more than very secretive and it took years before he won the trust.

A Dilemma

After seeing himself in the Kunst & Kontext Magazine (Issue 08, 2014, page 50) Koulé Ziehouo Coulibaly borrowed a bicycle and went to see a diviner ouside of Korhogo, who had a Tugubele couple (Abb. 9) from his hand. Ziehouo wanted me to show this couple, it was his best work. He did not remember when he had carved these two large size statues, but he said both spirits should symbolize the Senufo family. Meanwhile the diviner had painted bith figures of ritual backgrounds with paint. Ziehouo's work is filigree carved, it takes two weeks for a production. The now 77-year old does not distinguish between a production for a ritual use in his culture or between a production for a sale to an international dealer. He does not defferenciate, he always delivers a good and clean sculpture, because as a Koulé carving represents his livelihood.

The dilemma is that we make a distinction between what we believe to be an authentic work. The black stain treatment and also a paint job on the surface of an old object are authentic for the treatment in ritus. The so-called airport-art might get treated with furniture polish to look old and used. Once I bought such a Kpelié mask (Abb. 9, right) from Ziehouo for € 28,- in an instant purchase on Ebay. Ziehouo identified this mask a his recent work and he still remembered the French trader he sold the mask to. This mask does show the same quality in carving than a comparable mask (Abb. 9, right) Ziehouo made for the ritus. But such an Airport-art mask is frowned upon and treated derogatory. Once addressed by a collector on my aorport-art pieces, I received the statement, with masks like that, he doesn't want to have fleas in his house. At the same time, such a mask demonstrates the ability and, throught repetition, preserves its culture. I'll give another concern: € 28,- for two weeks work, and at this price, others have earned with.

A Kpelié mask or even a Tugubele statue only receives authenticity and identififaction if it is not traded anonymously but with nameable and comprehensive affiliation. With my Senufo archive, I ll give all interested parties the possibility of comparison with "only" 27 documentated carvers. Wether antique or recent, authentic or airport-art: The African sculpture is meaningful in terms of ist creative will and the modern design consideration.

Content and photos: Markus Ehrhard, 25.09.2018

Literature:

- Kunst und Religion bei den Gbato-Senufo, Elfenbeinküste. Karl-Heinz Krieg und Wulf Lohse, Selbstverlag, Hamburg 1981

- Aus Afrika, Ahnen-Geister-Götter, Hamburgisches Museum für Völkerkunde, Jürgen Zwernemann und Wulf Lohse, Christian Verlag, Hamburg 1885

- Afrika Begegnung, Künstler Kunst Kultur, Artur und Heidrun Elmer, Viersen 2002

- Wenn Brauch gebrauch beeinflusst, Markus Ehrhard, Trier 2013

- Wenn Neuordnung Ordnung schafft, Markus Ehrhard, Trier 2016

- Wenn Urform Form bestimmt, Markus Ehrhard, Trier 2016

Abb. 1: Kpelié-Masken, Elfenbeinküste.

1.Reihe (immer von links beginnend):

Melié Coulibaly, Koulé aus Landiougou, gest. 1952.

Kadohogon Coulibaly, Koulé aus Bolope, gest. ca. 1953.

Zanga Konaté, Koulé aus Blessegué, gest. 1940.

Nahoua Yeo Quattara, Koulé aus Nafoun, geb. 1934, gest. 2013.

Wahana Dairassouba, Koulé aus Tiogo. Yêchikpleyégué, doppelgesichtige Kpelié.

Nono Koné, Koulé aus Tiogo, gest. 1970. Yêchikpleyégué, doppelgesichtige Kpelié.

2.Reihe:

Fédiofègue Koné, Fono aus Kolia, geb. 1913, gest. 1987. Frühe Arbeit.

Fédiofègue Koné, Fono aus Kolia, geb. 1913, gest. 1987. Frühe Arbeit.

Fédiofègue Koné, Fono aus Kolia, geb. 1913, gest. 1987.

Tiénlé Koné, Fono aus Landiougou, geb. ca. 1910, gest. 1993.

Gobé Koné, Fono aus Gbon, gest. 1951.

3. Reihe:

Fossoungo Dagnogo, Fono aus Kalaha, geb. ca. 1894, gest. ca. 1973.

Fossoungo Dagnogo, Fono aus Kalaha, geb. ca. 1894, gest. ca. 1973.

Fossoungo Dagnogo, Fono aus Kalaha, geb. ca. 1894, gest. ca. 1973. Spätere Arbeit.

Songuifolo Silué, Fono aus Sirasso, geb. ca. 1914, gest. 1986. Entstanden zwischen 1935 und 1939.

Songuifolo Silué, Fono aus Sirasso, geb. ca. 1914, gest. 1986. Entstanden zwischen 1970 und 1980.

Songuifolo Silué, Fono aus Sirasso, geb. ca. 1914, gest. 1986.

4. Reihe:

Ziehouo Coulibaly, Koulé aus Korhogo, geb. 1941. Maske für den Poro.

Zié Soro, Koulé aus Djemtene, geb. ca. 1945, entstanden 1990. Maske für den Poro.

Madou Coulibaly, Koulé aus Korhogo, geb. ca. 1940 in Nâdal, gest. 2014 in Korhogo. Airport-art.

Doh Soro, Koulé aus Djemtene. Frühe Arbeit.

Yalourga Soro, Koulé aus Ganaoni. Yêchikpleyégué, doppelgesichtige Kpelié.

5.Reihe

Doh Soro, Koulé aus Djemtene.

Doh Soro, Koulé aus Djemtene. Yêchikpleyégué, doppelgesichtige Kpelié.

Bakari Coulibaly, Koulé aus Dickodougou. Frühe Arbeit.

Bakari Coulibaly, Koulé aus Dickodougou.

Bakari Coulibaly, Koulé aus Dickodougou.

Bakari Coulibaly, Koulé aus Dickodougou.

Fake you!

As administrator of the Facebook-group LIVING WITH AFRICAN ART, I have a few thoughts and experiences I'd like to share...in the era of Fake News it is so very easy to say anything. Ok, we have freedom of speech, we have the social media where it is everyones right to say and comment, what he or she wants to communicate. So the idea of having a group, where people gather with the same interest can be a great thing.

In the past I did present many of my Senufo sculptures and also I did promote my three books and my online archive of Senufo carvers. What to say? Not a single piece that not got doubted or bashed down, not a single one! It is so very easy to say „Sorry, fake!“, isn’t it?

I never ever received a single proof, why my object should be a fake, not even a reference to a book. Sad but true, once commented as „fake“, the object stays as a fake.

There are so many online-experts who judge an object just by one picture or two. Ok, some objects cry out fake, no doubt about that and no doubt, that there are many fakes around. But a real expert has to hold an object in his hands and has to compare it with other objects. Thatˋs what I try to achieve with my online archive about Senufo carvers to provide the possibility to compare. In many of my blog articles you see me comparing objects, which I find essential in that whole discussion.

I received so many requests in the past, and collectors are upset, when I say, that I don’t give expertise just by an image. The next thing is, that the level of discussion does not stay on a well-mannered level. If you doubt the comment of someone, it easily turns into an insult on a private level (I once received an image from the anus of a collector titeling me an "asshole"...I got that message as a gay man, but no, not catchy...and no, not pretty).

In the beginning I did collect by provenance. After a while I found out, that there are way too many objects from an "old French Collection", where the owner doesn’t want to be named because of discretion. You really believe that? Come on!

So I specialized into objects, where the carver is known or to identify. Sure, all Senufo carvers did work for ritus, but also for making money by selling to dealers. Carving is their existence. That should be understood first and not judged in advanced.

As administrator of this facebook group LIVING WITH AFRICAN ART I am responsible for the way of communication. That’s written in the group discribtion and I said in certain comments, where it started to get out of hands, that this group is not about the discussion of authenticity.

In this group every enthusiast should have the possibility to show how he or she lives with tribal sculptures. And as the founder of this group, I am very happy to see colorful, different, enriching and inspiring lifestyles. That’s what is this all about.

Thank you!

Yours

Markus

Notation on my own behalf:

After this article on my website and as a post in my group, I verbally got insulted by certain "online experts" again. I was about to share their verbal assaults and they threatened me with consequences "I can not imagine". I deleted the whole content and deleted the group. This behave not only shows the manipulative and disturbing intention of these persons, to me this has a criminal force.

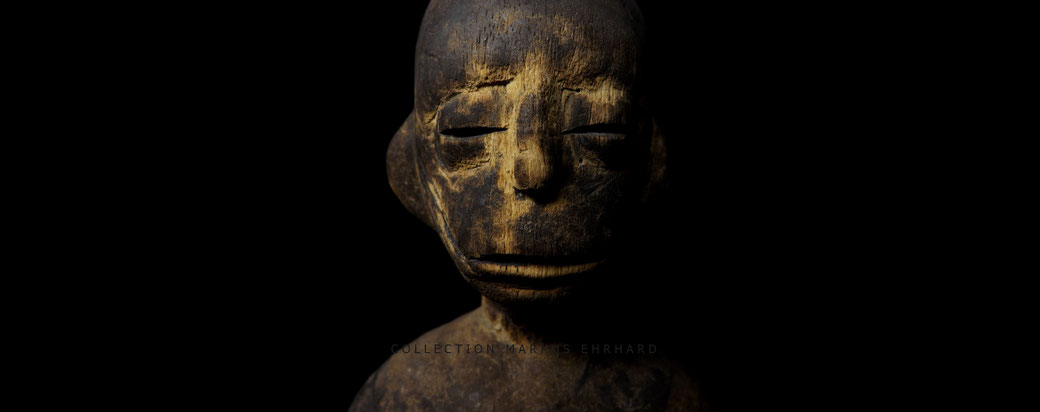

The black stain treatment

Tugubele woman, carved by Sabariko Koné, Koulé from Ouézomon. Woman: 24,0 x 6,5 x 6,0 cm, wood. Collected by Dramani Kolo-Zié Coulibaly 2016 in Boundiali, belonged to the Tugubele convult of a Sando diviner in Ndara.

Literature:

- Wenn Urform Form bestimmt, Markus Ehrhard, pages 20 - 23, 122 - 125.

- Kunst und Religion bei den Gbato-Senufo, Elfenbeinküste, Karl-Heinz Krieg und Wulf Lohse, pages 29 - 30.

- Afrika Begegnung, aus der Sammlung Artur und Heidrun Elmer, pages 28 - 29.

- Aus Afrika, Ahnen - Geister - Götter, Jürgen Zwernemann, Wulf Lohse, pages 68 - 69.

- Kunst & Kontext, Ausgabe 4 2012, Dr. Andreas Schlothauer, pages 4 - 10.

In former blog articles I already said, that dirt is not patina. Patina are surfaces on an object that changes during the process of making and over the years of aging. These surfaces are set together by colour and colour fading, structures and textures, traces of treatments (like sacrifications or the black stain treatment) or by traces of usage like wear, abrasions and even damages.

There are many misunderstandings when it is about patina on Senufo sculptures. Very often I hear the information about a mask or statue, that the object got sacrified with blood from a goat or chicken. This is wrong. It is right that the Senufo do sacrifications, but not directly on a sculpture. There is only one exception at the Senufo sub group of the Wanebele called kapaquatianh, carved fetish heads that receive a cover with animal blood.

Very typicial and sign for an authentic Senufo mask or statue, is the so-called black stain treatment. Beside the facts, that this handling protects the object from insects infestation and makes the wood durable against moist and usage, the black stain treatment is part of a ritual act. The treatment gives an object spiritual power.

The Senufo carvers from the Koulé and the Fono, and also the Sando diviners, treat wooden objects with this multistage treatment: After a statue or a mask is carved and sanded, the objects receive a coat of the juice from the roots of the red root plant, also known as mallow plant (lat.: malvaceae). Then the covered object is getting packed with a ferrous clay. After dried in the sun, the clay is getting wahsed off. The containing iron caused an oxidation of the red wood juice and the surface will become black. This dark layer can be chunky and crusty, but also be like a varnish smooth and glossy coating.

Sidekick Information: On old objects the wood shines orange on scuffed corners and edges. The wood on recents objects appears white throught this covering.

The Tugubele women made by Sabariko Koné (+1949) from Ouézomon after 1930 on the top image has an excellent fine black coating caused by the described stain treatment. The image below shows a Kpelié mask carved by Fossoungo Dagnogo from Kalaha around 1940. The black stain treatment does show a black coating, some parts shine like a thin varnish other parts are scoured by usage.

In case the black coating peels off after years of usage, sometimes the sculptures will get colored with paint to receive new spiritual power. Rarely but it can also be the case, that an object is getting washed and sanded to take away the power. But careful, mostly the object should look used to achieve a better price and we talk about manipulation.

Kpelié mask, carved by Fossoungo Dagnogo, Fono from Kalaha. *1894 +1973. Time of creation around 1940. 29,5x 14,0 x 6,0 cm, wood. Collected by Karl-Heinz Krieg.

Literature:

- Wenn Brauch Gebrauch beeinflusst, Markus Ehrhard, page 92 - 93.

Content and images by Markus Ehrhard, 02.08.2018

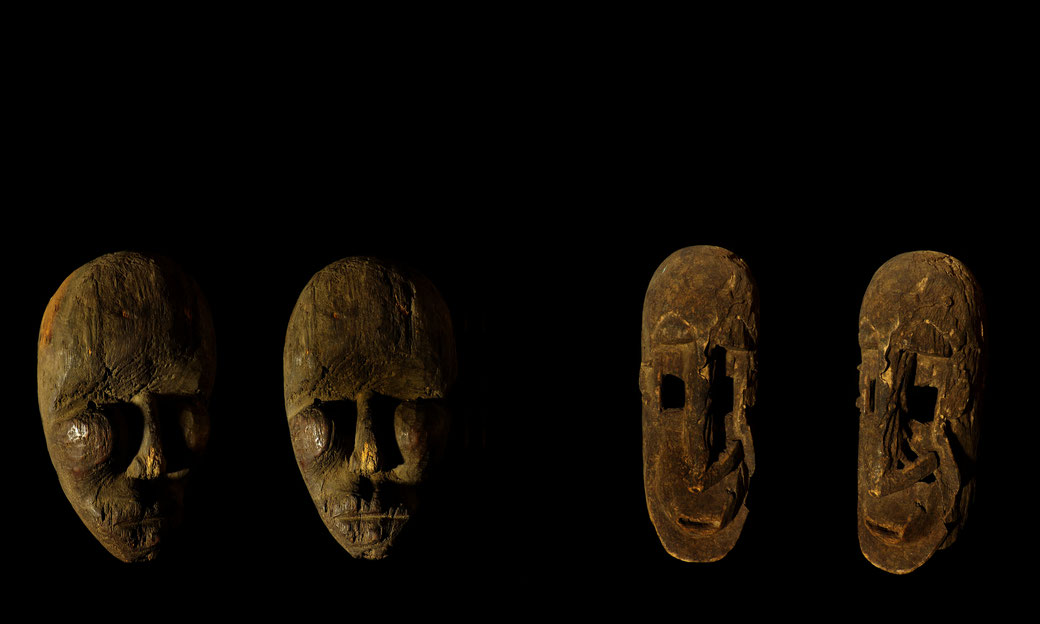

A carver with two faces - Yalourga Soro

Over the years of collecting Kpelié masks of the Senufo tribe, I had the opportunity to see a huge number of masks of certain carvers. Sometimes it is easy to identify or determine the soucre of origin, sometimes a mask or statue made by a known carver is completely different to an object made from the same hand. Keeping in mind that some carvers worked for more than 60 years certain styles, shapes and proportions evolve and can change fundamentally.

In their lifetime Senufo carvers could be very productive. More than 1.000 objects from a small statue up to a large piece of furniture made by just one man is not uncommon, keeping in mind that the guys started carving at an age of 12 or even younger. By collecting a number of pieces from one carver over the years, you learn to see the development, observe the change of the artistic awareness, exposing the strengths and the weaknesses, pointing out the own handwriting and character.

Yalourga Soro was a Koulé from Ganaoni. His available dates of birth and death can not be accurately be determined. He was the same generation as Songuifolo Silué (1914-1986). Yalourga was very productive in a long lifetime. It can not be verified if Yalourga did learn directly as a student, but he provably was influenced by Sabariko Koné in his figurative statues (read my article: The Sabariko-Koné-Standard). Yalourga worked in the classic Ouézomon-style, but also, like Songuifolo Silué, in a pure and reduced style later in his lifetime.

A larger number of Tugubele couples (as separate male and female statue or male and female Tugubele are fixed together on a base) are known. They all show differences in their faces. Every Senufo carver does focus especially on the faces and heads to show that the statues belong together as a couple and to show that they have the same spiritual power. But this "weak point" in the creative work of Yalourga Soro becomes a character and a distinctive feature. His notion and conception for the shape of a body and body volume is deformed. One horse rider statue is known where the horse does look like anything else but not like a horse.

His double faced Kpelié mask stands in complete opposite to this understanding of shape and proportion. There are only six other Senufo carvers in this archive, where it is documentated, that they carved the double faced Kpelié (Bakari Coulibaly from Dickodougou, Ziehouo Coulibaly from Korhogo, Wahana Dairassouba from Tiogo, Nono Koné from Tiogo, Zanga Konaté from Blessegué and Doh Soro from Djemntene), but the masks from Yalourga Soro are the most precise masks when it comes to the symmetry of both faces. And, from my point of view, I can not name another carver who produced that many double faced masks (just one of the seven masks in my collection does have a single face).

The Yêchikpleyégué (Senufo name for the doublefaced Kpelié) is danced on public celebrations when twins are born. Everyone in the village is allowed to see this mask dancing and entertaining. Explanations about the doublefaced Kpelié in literature vary. Burkhard Gottschalk describes a bisexual symbolism in these masks, but the Senufo do not differenciate between sexual orientations. Karl-Heinz Krieg did document in several interviews with the carvers, that it is a sign of an intelligent sculpturer that he can carve two faces. It is like what we call a "Geniestreich" in Germany, an exception, only a very talented carver is able to do. In conversations I held, the answers in chorus where that the Yêchikpleyégué is danced to celebrate the birth of twins and that the spirits have two faces to give power and support the life of the new born ones.

For sure it is to say, that Yalourga's strength is the doublefaced Kpelié. In general it can be said, that his masks are nearly miniature like and tiny according to masks of the same genre of the other carvers. Comparing his masks in an own overview, their different stages of development are interesting to look at. He always carved with all the traditional features of a Kpelié, also named as Ouézomon-style. But, like Songuifolo Silué, Yalourga developed his own pure style in his masks, but not in his statues. The decoration elements are plain in these masks and not decorated with rills or carved hatchings. Obviously this reduced style is of importance when a carver is getting older and his eyesight gets weary.

Also a very characteristic feature of his work is the finish. Nearly all his masks show a greasy surface. He treated his masks with Karité butter. So the overview of these authentic masks does show certain stages of usage and patina. Some masks are completely covered with the black lye treatment, some have a crusty surface, other masks are like sanded, and the very old mask of Yalourga (first one on the left) does even show natural red Pigments, persumibly extracted from a plant.

I really would like to find out more about this interesting Senufo carver. Relatives, who still live in the area of Ganaoni, don't want to provide any information about Yalourga Soro for whatever reason.

Find more objetcs and information about Yalourga Soro in his profile:

African patching

There are certain signs and indicators, that an African sculpture is used in the tribe. Traces of usage and, determined by the treatment, diverse kinds of patina are to mention. Depending on the filigree character and making of a sculpture damages of limbs and fragile elements can also be a sign for authenticity. Even when some major parts of an object might be injured or are even lost.

In the tribal use a damaged object often, not always, is not of value anymore, because it might have lost its spiritual power. In case of the Kpelié mask from the Senufo, a chipped mask with missing elements is decribed as the "ugly" mask and gets scoffed while dancing (from: Kunst und Religion bei den Gbato-Senufo, Elfenbeinküste, Karl-Heinz Krieg und Wulf Lohse, page 68).

Important objects, that have damages receive a repair or patching on spot. It can be case that a mask is used over years and receives a correction later on. Or, that there are corrections in the process of making, when there are misshapps in carving or casting. It is not easy to identify these reparations. It is of importance, that this reparation took place right on the local spot, that is why this kind of repair is called "African patching" ("Afrikanische Reparatur").

The right horn broke off the above shown Kpelié mask from the region of Dickodougou (left image). In ritus this mask would have lost all its spiritual power. So, because of certain importance of that mask, the horn got repaired with a cuff made of a brass sheet.

In the casting process of the iron Dogon mask (right image), the metall did not merge at the part of the mouth and left sharp edges. An additional clasp of the same material did repair the object.

Sidekick information: There are some dealers who tell you, that chipps and cracks on a sculpture are signs of usage and indicator of an authentic piece. Even damages can be faked and deliberately caused. So that argument is totaly baloney. But more worse: Try to sell for example a damaged Kpelié mask with a missing decoration element as a collector. I guarantee, that no one, believe me, NO ONE will ever buy your injured object, because it has no value.

Images and text by: Markus Ehrhard, 28.01.2018

Kpelié mask, region of Dickodougou.

29,0 x 15,5 x 9,0 cm, wood, African patching at the right horn.

Literature:

- Wenn Neuordnung Ordnung schafft, Markus Ehrhard, pages 140 - 141.

- Kunst und Religion bei den Gbato-Senufo, Elfenbeinküste, Karl-Heinz Krieg und Wulf Lohse, page 68.

Dogon mask.

28,0 x 18,5 x 6,0 cm, iron, African patching with iron clasp at the mouth.

Literature:

- Wenn Brauch Gebrauch beeinflusst, Markus Ehrhard, pages 40 - 41, 200 - 201.

Not wonderful - but powerful

In case you collect Senufo sculptures, sooner or later you come along small quirky figures:

They are called Gniniguefobele, small bronze, bras or, since 1950, aluminium statues casted in lost wax technique. They are created by the Fono, Senufo black smithers, in large quantities. Their size is between 2 cm to 10 cm.

The Sando deviner hands these statues to a person who needs protection as a kind of medicine. Sometimes a person wears a whole bunch of these spirits as a bracelet, anklet or in a small leather pouch, sometimes a person wears only one as a necklace. They stay with an owner for his whole lifetime. Also they are devices for the deviner itself. These little statues belong to the Tugubele, but are an own genre of spiritual meaning and have an enormous spiritual power. Also there are animals as statues or pendants, like the chameleon or the turtle, or miniatures of anklet jewelry with the same meaning and power.

The Senufo statues and masks are known for beeing very elegant. These little guys are everything else than beautiful. It would be possible to create a more distinguisehd, a more graceful figure. But in this case, the Gniniguefobele, are not ment to be human or humanlike. They are an idea of how a spirit could look like with forceful power. It is not an abstraction of the human body.

There are many voices in the collectors scene who are very quick in saying, that these statues are made for selling as Airport-art. There are larger statues casted in metal made for selling. But there is such a huge demand handing out these spirits to people, who need their power, that in most cases you will find an authentic piece. Generally they are not valued in the collectors scene, because they are not beautiful. After usage, they usually get sold. You can find them on trade markets even in Kenia. Prices range from € 10,- up to € 100,- per statue.

Gniniguefobele statues published in:

Wenn Urform Form bestimmt, Markus Ehrhard, 2016. Seiten 78 - 85.

Images and text by: Markus Ehrhard, 28.01.2018

Genres of the Kpelié: The Dioula mask

The Dioula form an own Senufo Group with an Islamic background. Dioulas can be part of other sub-groups of the Senufo. Songuifolo Silué for example belonged to the Kafibele and was also a Dioula. He lived and worked in Sirasso, which is the Dioula name of the village, Solokaha is the Senufo name.

The Massa cult in the 1950 did destroy a lot of Senufo sculptures, it was not allowed to produce or have objects with a face. But masks and statues made after that time are carved in the old traditional style with the same symbolism, force and power.

As written in former articles about the Kpelié, in the last 150 years, the typical features didn't change in its fundamental style. But Kpeliés made by and for the Dioula group show a significant distinction, they are larger than the traditional Kpelié.

The above shown mask, carved by Songuifolo Silué in his pure style, is evidently larger than other Kpeliés. But the minimal style has nothing to do with the size. Karl-Heinz Krieg did date this restored mask around 1960. Beside this authentic mask with traces of usage, two other masks are known. One is in the private Karl-Heinz Krieg collection and one is exhibited at the Museum für Völkerkunde in Hamburg, Germany.

Kpelié mask, carved by Songuifolo Silué, Fono from Sirasso. *1914 +1986. Time of creation around 1960.

31,5 x 19,5 x 8,0 cm, wood, partly restored. Collected by Karl-Heinz Krieg in the 1960ies.

Literature:

- Wenn Neuordnung Ordnung schafft, Markus Ehrhard, pages 122 - 125.

- Kunst und Religion bei den Gbato-Senufo, Elfenbeinküste, Karl-Heinz Krieg und Wulf Lohse, page 46 - 49.

- Aus Afrika, Ahnen - Geister - Götter, Jürgen Zwernemann und Wulf Lohse, Seite 65 - 66.

- Hamburgisches Museum für Völkerkunde, page 14.

- Afrika Begegnung, aus der Sammlung Artur und Heidrun Elmer, page 67.

Copyright content and images by Markus Ehrhard, 03.08.2017

Gernes of the Kpelié: The Calao hornbill mask

The legend of the Calao says, that this hornbill bird picks at a man's forehead to give him power, knowledge and wisdom. So every Kpelié in wood or metal does have this center mark. Sometimes you read definitions, that that this mark is a sacrification or even a beauty mark.

At the Senufo culture, there are Calao statues from very small (from 7 cm) up to human size known. These smaller statues are used by a diviner, larger ones can be placed at a dancer's head. Antique statues show the traditional black stain treatment, birds carved after 1950 can be painted in white with some ornaments, recent ones are partly covered with bras plates (mostly used in Airport-art to make the object look dramatic, these metal plates have no meaning in ritus).

The Calao is one of the archtype animals in Senufo culture. His portraiture is mostly very stylized and kind of abstract. There are many classic Kpeliés known with a Calao bird as center top. But the two shown masks represent an own genre: The Kpelié with a Calao head and a very long peg of the hornbill, that covers the complete face.

Both masks shown are recent masks and came from the region of Korhogo. The right one is carved very simple, the end of the peg touched the nose tip and is fixed. The peg at the left mask stands free without any attachment at the face. Masks of this genre usually are very impressive and demand skill and ability by the carver.

I could not clarify till today, what the exact use, meaning and symbol of this genre is. Or this type has an own name or association. It is not confirmed, that these masks dance at the Poro only. Everyone I asked tells me, that this type represents power and wisdom. I persume, that these masks were danced at harvest festivals, because a properous farmer has a lot of sageness, when he picks a huge yield.

Left:

Kpelié mask, carved by an unknown carver, region of Korhogo.

32,0 x 15,0 x 13,5 cm, wood.

Literature:

- Wenn Urform Form bestimmt, Markus Ehrhard, pages 106 - 107.

Right:

Kpelié mask, carved by an unknown carver, region of Korhogo.

32,0 x 14,0 x 10,0 cm, wood.

Literature:

Not published yet.

Copyright content and images by Markus Ehrhard, 02.08.2017

Genres of the Kpelié: The Antilope mask (?)

Upfront: I have no final explanation or committed description of this certain genre. Over the years of collecting Kpelié masks, I observed the characteristica of a center top placed Tugubele (I persume it is a Tugubele spirit), that in most cases holds long horns. Mostly the horns are ripped and sometimes twisted. I assume that these horns belong to a kind of antilope, because shape and structure are different to a caddle or buffalo of the Senufo. The Kpelié by Bakari Coulibaly has in addition two ears below the horns.

It is quite obvious, that the faces of this genre are diverse to the classic face of the Kpelié. In case of the mask carved by Bakari Coulibaly, I would not have had the idea, that this is a Kpelié. The Kpelié made by Ziehouo Coulibaly is closer to the classic Kpelié, but he differentiated also in the elongated silhouette and in a face with a very spiky chin. Ziehouo also carved the spirit on top holding the horns with his big hands. Accentuate this scenery it is for sure, that this is a symbol for something. I persume it should show the power of a spirit over animals or a kind of a hunting scene.

There is the association of the Nokârigâh known. They are a kind of healer and omniscient observer. As a symbol the Nokârigâh wear a ring with a buffalo head, which is different to the design a features of these masks. I never received an answer or closer information about this special genre.

Left:

Kpelié mask, carved by Ziehouo Coulibaly, Koulé from Korhogo.

37,0x 16,5 x 8,5 cm, wood and paint.

Literature:

- Wenn Neuordnung Ordnung schafft, Markus Ehrhard, pages 170 - 173.

Right:

Kpelié mask, carved by Bakari Coulibaly, Koulé from Dickodougou. 37,5 x 15,0 x 11,0 cm, wood.

Literature:

- Wenn Urform Form bestimmt, Markus Ehrhard, pages 156 - 159.

Copyright content and images by Markus Ehrhard, 27.07.2017

Genres of the Kpelié: The piper

Similar to the Kpelié of the genre of the acrobat is the piper. He is also an entertainer and every one in the area is allowed to see this mask on public celebrations. His character is polite and friendly. The mask of a piper is, like the acrobat, not common. It is more of importance that the Kpelié shows beauty and elegance than a certain nature or temper.

Where as the decoration elements and the center tops are identical as the features of the classic Kpelié, the expression of the face is different. The cheeks of the piper are ballooned and the mouth is pointy and elongated. The presented mask is a typical example for this character. The shiny surface got treated with Karité butter and the masks smells sweet.

Kpelié mask, genre of the piper. Unkown carver.

32,0 x 15,0 x 9,5 cm, wood.

Literature:

- Wenn Neuordnung Ordnung schafft, Markus Ehrhard, pages 152 - 153.

Copyright content and images by Markus Ehrhard, 17.07.2017

Genres of the Kpelié: The acrobat

In generell, the Kpelié mask is a mask that should entertain, it is not an evil or bad mask. In some books you can read the definition, that the name itself means face on an acrobat or comedien. But talking to carvers, they all say, Kpelié is a face of wood.

But certainly one of the genres of the Kpelié is the character of the entertainer. Everyone at the venue, like a harvest fest, is allowed to see this character, who has acrobatic elements in his perfomance.

The mask obove does show a bended male body as center top. Obviously the acrobat: The figure can hold its head between his knees. Also interesting is the cotton fabric. Narrow stripes from Sudanese weaving loom are handstitched, edge on edge, together and amount to large scarf that covers neck and shoulders of the dancer. The ruged cotton, parts are colored blue, is very soft.

Kpelié mask, genre of the acrobat. Collected by Souleymane Arachi, Korhogo, in San, region of Tingrela.

14,0 x 7,5 x 6,0 cm, wood, cotton cloth.

Literature:

- Wenn Neuordnung Ordnung schafft, Markus Ehrhard, pages 148 - 151.

Copyright content and images by Markus Ehrhard, 10.07.2017

Genres of the Kpelié: Kids masks

For a long time, these small Keplié masks were wrongly described as "passport masks" or even as Airport-art, because they could not be specified. Karnigi Coulibaly, the carver of the wooden mask on the right, did say in an interview with Karl-Heinz Krieg in 1968, that these masks are danced by children before the beautiful Kpelié is going to perform by an adult dancer and they should enterrain the audience.

Another speciality is, that the children did hold these masks in their hands while dancing. These rare masks don't show attachment wholes. The masks were not fixed with straps to the forehead. The small Kpeliés were made by a Koulé as well as by a Fono.

Left:

Kpelié mask for children, casted by Fono Fédiofègue "Fedi" Koné, Fono from Kolia. *1913 +1987. Early work, time of creation between 1940 and 1950.

17,0 x 10,0 x 5,0 cm, bronze alloy.

Literature:

- Wenn Brauch Gebrauch beeinflusst, Markus Ehrhard, page 138 - 141.

Middle:

Kpelié mask for children, casted by Fono Fédiofègue "Fedi" Koné, Fono from Kolia. *1913 +1987. Early work, time of creation between 1940 and 1950.

19,0 x 9,0 x 4,5 cm, bronze alloy.

Literature:

- Wenn Brauch Gebrauch beeinflusst, Markus Ehrhard, page 138 - 141.

Right:

Kpelié mask for children, carved by Fono Karnigi Coulibaly, Fodonon. Time of creation 1967. Former Karl-Heinz Krieg Collection.

14,0 x 7,5 x 6,0 cm, wood.

Literature:

- Wenn Brauch Gebrauch beeinflusst, Markus Ehrhard, page 90 - 91.

- Kunst und Religion bei den Gbato-Senufo, Elfenbeinküste, Karl-Heinz Krieg und Wulf Lohse, page 44 - 45.

- Afrika Begegnung, aus der Sammlung Artur und Heidrun Elmer, page 44 - 45.

Copyright content and images by Markus Ehrhard, 07.07.2017

Genres of the Kpelié: The double faced mask

In about one of ten Kpelié masks you will find the double faced mask, Yêchikpleyégué in Senari. In literature you can read, that this genre does show bisexuality. But the Senufo do not differentiate or discriminate between sexual orientation. Karl-Heinz Krieg told me, that this genre is made by intelligent Senufo carvers. Only a smart carver can deal to create two identical faces. This interpretation depends on the region. It is noticeable, that many of the doublefaced Kpelié show a Tugubele couple or a single female Tugubele spirit on top.

It is for sure to say, that the double faced mask is dancing on the event to welcome twins. Everyone in the village can see the mask. The dancing double faced Kpelié is a symbol of the celebration and protection of the twins life.

It is a challenge for a Koulé to carve two identical faces side by side and for sure it demands a smart carver to do this. So Karl-Heinz Krieg's explanation is logic. It also demands a lot, to carve identical Tugubele couple, where is there is differenciation between a male a female statue. The Kpelié alsways is a male character, so both faces have to be absolutely identical.

Doh Soro, a Koulé from Djemtene, who is famous for his maternité statues, rarely carved masks. So his double faced mask is the only one known made by his hands.

There are certain Koulés especially famous for the double faced mask. Althought Yalourga Soro, a Koulé from Ganaoni, was eminent for this genre, there are no single faced masks known. Yalourga had problems to carve an identical Tugubele couple. But his small masks are delicate and his faces are absolutely identical.

Nono Koné, a Koulé from Tiogo, who died 1970, did carve this classic doublefaced Kpelié with the Tugubele couple on top. Their meaning is a matter of conjecture and is not clarified.

Left:

Yêchikpleyégué, double faced Kpelié mask, carved by Doh Soro, Koulé from Djemtene, region of Korhogo.

34,0 x 18,0 x 9,5 cm, wood.

Literature:

- Wenn Neuordnung Ordnung schafft, Markus Ehrhard, pages 116 - 117.

Middle:

Yêchikpleyégué, doublefaced Kpelié mask, carved by Yalourga Soro, Ganaoni. Early work.

32,5 x 11,5 x 5,0 cm, wood.

Literature:

- Wenn Neuordnung Ordnung schafft, Markus Ehrhard, pages 144 - 145.

Right:

Yêchikpleyégué (doublefaced Kpelié) mask, carved by Nono Koné, Koulé from Tiogo.

34,5x 18,0 x 9,0 cm, wood. Collected by Karl-Heinz Krieg. Time of origin around 1950.

Literature:

- Wenn Brauch Gebrauch beeinflusst, Markus Ehrhard, pages 118 - 119.

- Wenn Urform Form bestimmt, Markus Ehrhard, pages 24 - 25, 40 - 41.

Copyright content and images by Markus Ehrhard, 30.06.2017

Genres of the Kpelié: The Poro mask

First it is important to distinguish, who is allowed to see the dance of the Kpelié mask: The Senufo diversify between a mask, that can be seen by everyone living in the place or only by the members of the Poro, the secret society of men. The distinction depends on the social gathering. The Kpelié can be danced at an event where the birth of twins is getting celebrated, at a harvest festival or on a funeral. Everytime the Kpelié represents a male, never a female, spirit. In some books you can read, that this mask does show an ancestor, but that is not confirmed.

The most common mask is the Kpelié with the Capok fruit on top, which is the symbol of the occupational group of the Koulé. It can not be said, that certain center top features are for special celebrations only. In some books it is written, that a mask with the Capok fruit on top only dances on a funeral of a Koulé. That might be the case, but masks with that symbol also dance on other events like on harvest festival.

The above shown mask on the right from Zié Soro, Koulé from Djemtene, did dance on funerals or on celebrations at the Poro. Only men of that secret society were alowed to see that mask. This classic Kpelié does also have features like the two smaller Kpelié masks and typical geometric decorations at both sides. Zié told me in an interview, that he carved this mask 25 ago for the Poro of Djemtene. And that the two smaller faces are symbol for a mask of his occupational group and of the Koulé of his generation.

The Kpelié in the middle is carved by Ziehouo Coulibaly, Koulé from Korhogo and shows the same features like the mask from Zié Soro and as same as from the mask made by an unknown carver from the region of Korhogo.

Left:

Kpelié mask, carved by an unknown carver for the Poro, region of Korhogo.

32,0 x 15,5x 8,0 cm, wood.

Literature:

- Wenn Urform Form bestimmt, Markus Ehrhard, pages 102 - 103.

Middle:

Kpelié mask, carved by Ziehouo Coulibaly, Koulé from Korhogo, for the Poro.

28,5 x 13,0 x 7,5 cm, wood.

Literature:

- Wenn Neuordnung Ordnung schafft, Markus Ehrhard, pages 174 - 175.

Right:

Kpelié mask for the Poro, carved by Zié Soro, Djemtene. Date of origin around 1990.

32,5 x 15,0 x 7,5 cm, wood.

Literature:

- Wenn Neuordnung Ordnung schafft, Markus Ehrhard, page 160 - 164.

Copyright content and images by Markus Ehrhard, 28.06.2017

Closer look: The Kpelié mask

The Kpelié mask is the best known and most famous mask of the Senufo culture. The original word is "kpeli yehe". The translation of these words are not clarified. In some books you can read "face of an acrobat, dancer or comedien", speaking with the carvers, their translation is "face of wood". The Kpelié always represents a male spirit, there are no female Kpelié masks.

The Kpelié can be carved by the occupational group of Koulé in wood and by the occupational group of Fono in wood or in metal, like bronze, bras or, after 1950, in aluminium. A Daleguee is a Koulé carver, who is called by the Tugubele spirits to carve the Kpelié. No matter casted in metal or carved in wood, the Kpelié serves different purposes. Every village does keep a number of Kpelié masks, wrapped in tissues, in the "Case sacrée", a house/shrine, for ritual trade. Every seven years the diviner asks the Tugubele spirits about the power of the masks. Some receive treatment with colour to gain more power, other masks are getting sold, when they have no power anymore. These masks get replaced by new masks made by the local carver or blacksmither. It is possible that masks come from other regions, but never from a different of the 30 sub-Groups of the Senufo. So the Kpelié is not a rare mask. There were and are large quantities needed in ritual usage and even more are produced as Airport-art articles.

All Kpelié masks show the follwing characteristic features, some vary because of the skills and abilities of the carvers (read also the article about "Masterpiece vs. ordinary") , by the region and time of creation. There are pure masks with all typicial elements and masks overloaded with decoration features, which is the very own interpretation of a carver. There is a competing situation between the carvers, the one with a beautiful and impressive mask will receive respect and reputation, and will have more orders. Althought there were Christian and Islamic influences (the invation of the Massa cult after 1950) in Senufo life, the Kpelié style didn't change dramaticly since about 150 years. Till today, the Kpelié is danced in ceremonies.

Most remarkable is the elongated face with the half closed eyes, half-circle eyebrows and a long t-shaped nose. In the region west of Korhogo the mouth is rectangular shaped, filled with a right-angular hatching. The Senufo don't wear lip-pegs today, it is said, that their ancestors were wearing lip-pegs. So the mouth of a Kpelié always has an underlip peg. Beside the nose there can three or five furrows that represent facial scars. Every Kpelié has an oval shaped stigma on the front. This mark was caused by the Calao bird, when he gave power and knowledge to the spirit by picking with his bill on the forehead. On some masks this scenery is illustrated at center top, featuring an abstract bird or a head with a very long hornbill. Talking about center top there is a huge variety on symbols, that represent certain attributes of the Senufo: The Capok fruit, which is used by the Koulé only, because it is a symbol of their occupational group. Then there are Tugubele couples (mostly on the double faced Kpelié, the Yêchikpleyégué), a single female Tugubele or just a head of Tugubele spirit. Recent masks, made after 1950 can display the chameleon. Older masks can have a geometric symbol or, in the region of Bolopé, a wing shaped object as center top.

The side decorations can vary in geometric forms from circular, rectangular, triangular or fantasy shaped. Sometimes they are plain without any pattern. But there can be masks overloaded with all kind of design that are possible to carve. Beside the center top attributes, there can be horns from a cattle or buffalo carved upturned or pointing downwards. Rarely there are ears of an animal, persumibly of an antilope, featured. Some Kpelié masks have smaller Kpeliés on the left and right side. There are two explanations: One says, that the spirit can look in every direction. Zié Soro explained, that these little faces are a symbol of the Koulé of his generation in the region of Djemtene. Beneath the mouth there are so-called "leg pairs" in different shapes carved on every Kpelié mask. These pairs, sometimes wrongly described as chicken legs, are developed from certain hairstyles, bunches on the side of the head, of the Senufo women.

Collection of Kpelié masks from certain Senufo Carvers (from top left):

Fossoungo Dagnogo, Fono, Kalaha (b. 1894 – d. 1973); Fossoungo Dagnogo, Fono, Kalaha (b. 1894 – d. 1973); Fossoungo Dagnogo, Fono, Kalaha (b. 1894 – d. 1973), late work; Nono Koné, Koulé, Tiogo (d. 1970); Nono Koné, Koulé, Tiogo (d. 1970); Nahoua Yeo Quattara, Koulé, Nafoun (b. 1934 – d. 2013); Fédiofègue Koné, Fono, Kolia (b. 1913 – d. 1987), early work; Fédiofègue Koné, Fono, Kolia (b. 1913 – d. 1987), early work; Fédiofègue Koné, Fono, Kolia (b. 1913 – d. 1987); Tiénlé Koné, Fono, Landiougou (b. 1910 – d. 1993); Gobé Koné, Fono, Gbon (d. 1951); Songuifolo Silué, Fono, Sirasso (b. 1914 – d. 1986), time of creation between 1935 and 1939; Songuifolo Silué, Fono, Sirasso (b. 1914 – d. 1986), time of creation between 1970 and 1980; Doh Soro, Koulé, Djemtene; Zanga Konaté, Koulé, Blessegué (d. 1940); Bakari Coulibaly, Koulé, Dickodougou; Kadohogon Coulibaly, Koulé, Bolope (d. 1953); Melié Coulibaly, Koulé, Landiougou (d. 1952); Yalourga Soro, Koulé, Ganaoni, early work; Yalourga Soro, Koulé, Ganaoni; Zié Soro, Koulé, Djemtene (b. 1945), time of creation 1990; Ziehouo Coulibaly, Koulé, Korhogo (b. 1941); Ziehouo Coulibaly, Koulé, Korhogo (b. 1941); Ziehouo Coulibaly, Koulé, Korhogo (b. 1941); Ziehouo Coulibaly, Koulé, Korhogo (b. 1941); Ziehouo Coulibaly, Koulé, Korhogo (b. 1941), airport art; Ziehouo Coulibaly, Koulé, Korhogo (b. 1941), early work.

Copyright content and images by Markus Ehrhard, 27.06.2017

The yoghurt mask

There are people who swore on facial yoghurt masks, with the effect that the skin should look younger and fresh. But there are people who swore on yoghurt masks as "dramaticly different moistruizer" to fake wood looking old and used. No matter what you use, you get wrinkles anway, especially when you buy a fake object.

But how to tell, if an object got treated with yoghurt or other milk products with lactic acid bacteria that changes the surface of wood? How to decide, what is a crusty patina and what are nasty leftovers of milk product treatments?

You can't tell just by the surface, but you can tell by taking off splinters. Humidity has the strongest impact to change wood surfaces and structures over the time, but natural moist does not change the colour or structure of wood that dramaticly in a short time. When there are chips and splinters and the below wood is light, alsmost white or even greenish white, then you know, that the used wood is relatively fresh and young. Is that the case and only the surface looks blackish dark brown, then the object persumibly received a yoghurt treatment. The lactic acid bacterias destroy just the outside of the wood surface and make it look rotten, but don't destroy the inner part.

Old wood changes colour in the aging process. Oak wood for example will turn from off white to an orange shade. Other species of wood show a red, yellow or brown tone. See the Tugubele statue in the former article "First rule: Dirt is not patina - part 1".

The Kran mask and the Dogon mask above are typical examples where there was a treatment to make wood, even cracks, looking old and rotten. The colour of the wood under the surface is light and fresh. In the past, I did show these two masks to several people and the opinions where very different. Some described them as authentic, others said that they obviously are faked. We all know, if you ask 10 experts, you receive 10 different opinions. It was Karl-Heinz Krieg who explained me the manipulation with lactic acid bacterias on wooden objects.

Beside the treatment to make the Dogon mask looking old, this mask is also obvisously a fake, because it wont fit on your head. The back is too narrow.

Left:

Fake Kran mask, Ivory Coast.

29,5 x 18,0 x 10,5 cm, wood.

Literature:

- Wenn Neuordnung Ordnung schafft, Markus Ehrhard, pages 194 - 195

Right:

Fake Dogon mask, Ivory Coast.

34,5 x 15,0 x 21,0 cm, wood.

Literature:

- Wenn Neuordnung Ordnung schafft, Markus Ehrhard, pages 194 - 195

Copyright content and images by Markus Ehrhard, 11.06.2017

First rule: Dirt is not patina! Part 3

So often it is so difficult to tell, if an object is faked or not. As a collector, I always try to compare and find the differences on similar objects. And when you have two or more of the same genre, you start finding distinctions and variations, you wouln't have discovered on the single piece.

I thought to be on the safe side, I bought the chameleon, on the right, in an established gallery. It was sold to me as an authentic device of a Senufo diviner. The object was small in comparison to a mask or statue, I knew what is was and what it is used for. So I thought not to do someting wrong to buy a nice little piece in aluminium, knowing, that the Senufo use this very light but difficult to cast metal after 1950.

Later on I bought the left chameleon from my cooperator in Korhogo, Souleymane Arachi, also casted in aluminium. He received this object directly from a diviner in Korhogo and it shows typical signs of usage and abrasion.